Explore how major world religions view surrogacy from ethical, spiritual, and doctrinal perspectives. Understand the complex interplay between faith and assisted reproduction in this comprehensive guide.

In an era where science continues to redefine the boundaries of human reproduction, surrogacy has emerged as a beacon of hope for countless individuals and couples facing infertility, medical challenges, or social barriers to parenthood. However, as this assisted reproductive technology (ART) gains global acceptance, it simultaneously sparks profound ethical, legal, and spiritual debates—especially within the context of religious beliefs. For many, the journey to parenthood is not only a biological or emotional pursuit but also a deeply spiritual one, guided by centuries-old religious doctrines and moral frameworks.

This article explores the diverse religious perspectives on surrogacy, offering a nuanced understanding of how major world faiths interpret this modern reproductive practice. From Christianity and Islam to Judaism, Hinduism, and Buddhism, we delve into theological interpretations, ethical considerations, and evolving attitudes that shape religious communities’ responses to surrogacy. Whether you're a prospective parent, a healthcare provider, or a policymaker, understanding these perspectives is essential for fostering inclusive, respectful, and informed dialogue around reproductive choices.

The Rise of Surrogacy in the Modern World

Surrogacy—the process in which a woman carries and gives birth to a child for another individual or couple—has evolved significantly over the past few decades. Advances in in vitro fertilization (IVF), growing awareness of LGBTQ+ family-building options, and increasing rates of infertility have contributed to its rising popularity. Countries like the United States, Canada, Georgia, and some parts of Latin America have developed regulated surrogacy markets, while others maintain strict prohibitions.

Yet, despite its medical feasibility and legal recognition in certain jurisdictions, surrogacy remains a morally complex issue, particularly when viewed through the lens of religion. For billions of people worldwide, religious teachings provide the foundation for moral decision-making, including matters related to life, conception, and family. As such, religious doctrines often play a pivotal role in shaping individual and communal attitudes toward assisted reproduction.

Christianity and Surrogacy: A Spectrum of Beliefs

Christianity, with its vast denominational diversity, offers a range of perspectives on surrogacy. While no single, unified stance exists across all Christian traditions, common themes revolve around the sanctity of marriage, the integrity of natural procreation, and the moral status of embryos.

Roman Catholicism maintains one of the most definitive positions. The Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, in its 1987 document Donum Vitae ("The Gift of Life"), explicitly opposes all forms of in vitro fertilization and surrogate motherhood. The Church argues that procreation should occur exclusively within the marital act and that surrogacy separates the act of conception from the unitive bond between husband and wife. Furthermore, the creation and potential destruction of embryos during IVF is considered morally unacceptable.

“The child has the right, ‘in dignity and in truth, to be the fruit of the specific act of the conjugal love of his parents’,” the document states, emphasizing that surrogacy commodifies both the child and the surrogate.

Protestant denominations, however, display greater variation. Many Evangelical and conservative Protestant groups share concerns about IVF and embryo manipulation but may cautiously accept gestational surrogacy—where the surrogate is not genetically related to the child—under strict ethical guidelines. Mainline Protestant churches, such as the United Methodist Church and the Episcopal Church, tend to be more open, emphasizing compassion for infertile couples and the intentionality of family formation.

Orthodox Christianity generally discourages surrogacy, viewing it as an interference with God’s plan for conception. However, pastoral responses may vary, with some priests allowing case-by-case discernment, especially when medical necessity is involved.

Islam: Conditional Acceptance with Strict Boundaries

Islamic jurisprudence on surrogacy is deeply rooted in Sharia law and the preservation of lineage (nasab). Most Islamic scholars and religious authorities, including Al-Azhar University in Egypt and the Islamic Fiqh Academy, prohibit third-party reproduction, including surrogacy and donor gametes.

The primary concern is the disruption of bloodline and marital fidelity. In Islam, a child’s lineage must be clearly traceable to both parents, and any introduction of a third party—whether through egg, sperm, or womb—is seen as a violation of this principle. Surrogacy, therefore, is typically deemed haram (forbidden), as it involves a woman carrying a child not genetically her own, potentially blurring familial ties and inheritance rights.

However, some contemporary Muslim scholars and bioethicists have begun to explore nuanced interpretations. A minority opinion, particularly in countries like Iran, permits gestational surrogacy under strict conditions: the embryo must be created from the married couple’s own gametes, and the arrangement must be non-commercial. In Iran, such practices are legally permitted and regulated, making it a rare example of state-sanctioned surrogacy in the Muslim world.

Despite this, the majority of Sunni and Shia authorities remain cautious. The emphasis on marital privacy, the sanctity of the womb (rahim), and the fear of social confusion (e.g., accidental marriage between half-siblings) outweigh the desire to assist infertile couples.

Judaism: A Framework of Permissibility and Responsibility

Jewish perspectives on surrogacy are shaped by halakha (Jewish law), which prioritizes the mitzvah (commandment) of procreation. Unlike some other faiths, Judaism generally views assisted reproductive technologies, including surrogacy, more favorably—provided they adhere to specific religious guidelines.

In Orthodox Judaism, the determination of maternity is a central issue. There is debate over whether the genetic mother (who provides the egg) or the gestational mother (who carries the child) is considered the halakhic mother. Most authorities side with the genetic mother, meaning a child born via surrogacy using the intended mother’s egg would be considered fully Jewish if the mother is Jewish.

Surrogacy is often permitted when a woman is unable to carry a pregnancy due to medical reasons. However, ethical concerns arise around compensation, exploitation, and the treatment of the surrogate. Jewish law prohibits ona’ah (exploitation) and emphasizes tza’ar ba’alei chayim (avoiding unnecessary suffering), which extend to human dignity and fair treatment.

Reform and Conservative Judaism tend to be even more supportive of surrogacy, emphasizing compassion, inclusivity, and the right to build a family. These movements often encourage rabbinic counseling for couples considering surrogacy to ensure ethical and spiritual alignment.

Notably, Israel is one of the few countries where surrogacy is legally permitted and regulated, with specific provisions for heterosexual and, more recently, same-sex couples. The Israeli government even subsidizes IVF treatments, reflecting the cultural and religious value placed on parenthood.

Hinduism: Dharma, Karma, and the Ethics of Creation

Hinduism’s approach to surrogacy is less codified than in Abrahamic religions but deeply influenced by concepts of dharma (duty), karma (action and consequence), and purushartha (the goals of life, including progeny).

The desire for children is considered a natural and legitimate aspect of grihastha ashrama (the householder stage of life). Infertility is often seen as a karmic challenge, but not an insurmountable one. With the advent of modern medicine, many Hindus accept IVF and surrogacy as valid means of fulfilling the duty of parenthood.

Religious texts do not explicitly mention surrogacy, but ancient stories contain parallels. For example, the birth of the Pandava brothers in the Mahabharata involves divine intervention and non-traditional conception, suggesting that unconventional paths to parenthood are not inherently condemned.

However, ethical concerns persist. The commercialization of surrogacy—especially in India, which was once a hub for international surrogacy before banning it for foreigners in 2015—has raised questions about exploitation, the commodification of women’s bodies, and the spiritual well-being of all parties involved.

Many Hindu scholars and gurus emphasize ahimsa (non-harm) and seva (selfless service). A surrogate who acts out of compassion rather than financial desperation may be viewed more favorably. Additionally, the child’s jati (birth) and gotra (lineage) are important for religious rites, so clarity in parentage is essential.

Temples and spiritual leaders often encourage couples to seek puja (prayer) and darshan (divine sight) before undergoing surrogacy, seeking blessings for a healthy pregnancy and ethical conduct.

Buddhism: Compassion, Intention, and the Middle Path

Buddhism does not issue binding doctrinal rulings on surrogacy, but its ethical framework—rooted in the Four Noble Truths, the Eightfold Path, and the principle of ahimsa—offers valuable guidance.

The central question in Buddhist ethics is intention (cetana). If surrogacy is pursued with compassionate intentions—to alleviate suffering, fulfill a deep human desire for family, and act with mindfulness—it may be considered ethically acceptable. However, if driven by attachment, greed, or exploitation, it could generate negative karma.

Theravāda, Mahāyāna, and Vajrayāna traditions generally emphasize non-harm and the sanctity of life from conception. The destruction of embryos during IVF processes is a concern, as is the potential for psychological harm to the surrogate or the child.

In countries like Thailand and Sri Lanka, where Buddhism is predominant, surrogacy regulations have fluctuated. Thailand, once a surrogacy destination, tightened laws after high-profile cases involving exploitation and statelessness of children. Buddhist monks have called for greater ethical oversight, urging society to balance technological progress with moral responsibility.

Some contemporary Buddhist teachers advocate for a “middle way”—supporting surrogacy when it arises from loving intention and is conducted with transparency, fairness, and respect for all beings involved.

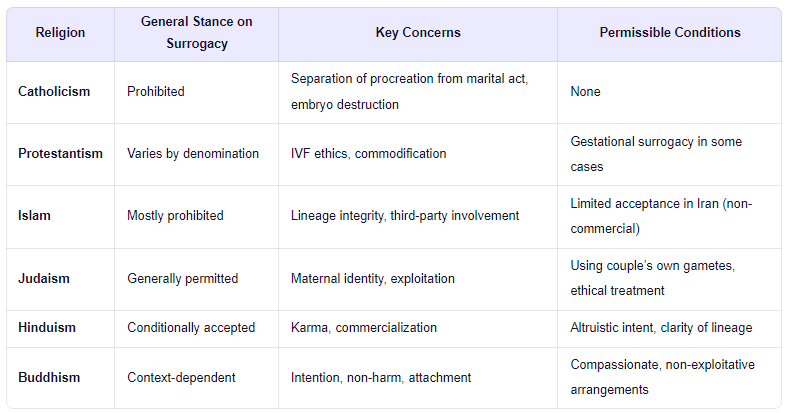

Comparative Summary: Key Religious Stances on Surrogacy

Toward a More Inclusive Future

As reproductive technologies continue to advance, religious communities are faced with the challenge of interpreting ancient texts in light of modern realities. While doctrinal differences remain, there is growing recognition across faiths of the emotional and spiritual dimensions of infertility.

Interfaith dialogues, bioethics councils, and pastoral counseling programs are emerging to help individuals navigate these complex decisions. Many religious leaders now emphasize compassion, discernment, and personal conscience over rigid dogma.

For policymakers and healthcare providers, understanding religious perspectives is crucial for designing inclusive fertility services, ensuring informed consent, and protecting the rights of surrogates and intended parents alike.

Conclusion: Faith, Ethics, and the Human Desire for Family

Surrogacy is more than a medical procedure—it is a profound human experience that intersects with identity, love, loss, and hope. Religious perspectives on surrogacy reflect deep-seated values about life, family, and the divine. While disagreements exist, many traditions share a common thread: the importance of intention, ethical conduct, and respect for human dignity.

As society moves forward, the dialogue between faith and science must continue—not in opposition, but in partnership. By honoring both spiritual beliefs and reproductive autonomy, we can create a world where the journey to parenthood is supported, respected, and accessible to all.

Whether guided by prayer, medical science, or both, the desire to nurture a child is a universal aspiration. And in that shared longing, there is room for understanding, empathy, and grace.